It’s funny how when writing about ancestors in the past, it seems easy to be objective and base stories on discovered facts. When writing about more recent people and events, the concern is a lack of objectivity. Having said that, I’ll continue with the story of Dad’s working life which will inevitably be from my perspective more than anything else.

Growing up in a railway home, you are aware of two things: the dominance of shift work and its impact on eating and sleeping habits, and the dangers facing the railway workers from day to day. Having read several railway staff files for family members, the department could be unforgiving with mistakes, fining men for any errors (however minor), and occasionally remunerating them for an innovation.

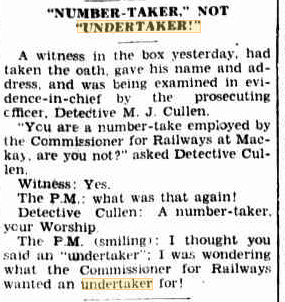

It’s likely that Dad started as a lad porter in the Queensland Railways, straight after Grade 10 and just before the beginning of World War II. He had brief stints in Landsborough and on the Gold Coast line, however he spent the bulk of his 50 years of railway service in Roma Street. Once he gained appointment as a numbertaker the rest of his working life was in the Roma Street (aka Normanby) shunting yards and he was working there by the mid-1940s. The usual response is “an undertaker??” No, though it could be argued there were times when the railways could have done with that occupation. In fact, a numbertaker is quite different and is also known as a tally clerk in some services.

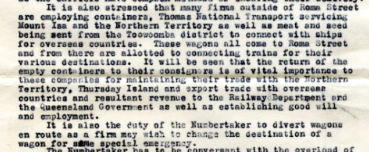

To this day I’m uncertain about the exact responsibilities of a numbertaker but my understanding is that his duties included checking the weight distribution of wagons and the sequence in which they were loaded, so goods could be off-loaded in the correct order. He could add columns of figures up, quick as a wink, in his head and I saw him do this many times. In fact, when I was struggling with mental arithmetic in Grade 3 or 4 it was Dad who managed to make me understand it, rather than the nun who taught me. The next level up in the ranking was a shunter, and Dad never wanted that job given its high risk. Whether something deterred him when he was young I don’t know, but I do know is that even as a young girl I knew when he’d come up devastated because some young bloke had lost his life or his limb during a shunting accident – and the significance of the injured man trying to feel his leg(s). During his life with the railway he saw this type of accident, and worse, more frequently than anyone would like.

Apart from the hazards of the shunting yard in and of itself (an occupation I’ve read in a journal is more dangerous even than mining underground), there was the lack of what we’d know as Occupational Health and Safety today. The men wore heavy navy blue serge uniforms which of course which made them nigh invisible at night or in bad weather. There were no high visibility jackets available at the time. Similarly, there was no arc lighting over the yards, rather the men carried a special type of kerosene lamp as they went about their duties. Imagine, if you will, these hazards combined with criss-crossing train tracks and the sheer tonnage of trains around them especially as they got further into their shift with associated tiredness. At a minimum they worked an eight-hour shift, walking between Roma Street and the Exhibition grounds. My mind boggles at how many kilometres and steps he’d have notched up on a Fitbit of today. In the 1970s, when he was in his 50s and we lived in Papua New Guinea, I remember there were many times when he worked extended shifts, sometimes as long as 16 hours. It has taken a long time, but I no longer get anxious with late-night phone calls – when we knew he was on shift it could strike fear in your heart.

During the war, the railways were a reserved occupation but before his death Dad told me how he’d had to supervise Italian POWs working near Corinda station. They would start early and work like crazy so they could “chill out” once they’d finished their duties. He always said that had he gone to war he’d have like to have been with the Ambulance Corps…he saw enough accidents that he knew he could cope.

Somewhere among my notes, he told me once about talking to a policeman about the events of the Battle of Brisbane. When the war finally ended, Mum told me he was pretty peeved to be on duty and unable to go into town to celebrate with the crowds.

Although Dad had learned to drive a car as a young man, we didn’t own a car until the late 1960s. He rode an ungeared pushbike to and from work every day….add that to the Fitbit tally! He would stop at the corner of our street before the hill, and wave goodbye – again part of that “you never know what will happen” concept.

All that fitness probably helped him a great deal aerobically and offset the effects of smoking at the time. However my own view is that his years on oxygen with emphysema had as much to do with coal dust in the yards as smoking. He caught pleurisy when he visited us in PNG in the early 1970s and our friend, the physician, said he had the worst lungs our friend had ever seen – full of coal dust.

On top of that he acquired industrial deafness, unsurprising in that environment, for which he was granted some compensation.

I mentioned the shift work which dictated our family activities to some extent. No air-conditioners then to offset a hot summer’s day in Brisbane when sleep was needed, and heaven help anyone who made lots of noise or who hammered on the door. Probably just as well we didn’t have a phone either! Throughout Dad’s working life, at least as I was growing up, his shifts rotated through 6am to 2pm, 2pm to 10pm and 10pm to 6am. He would then do three weeks of 2-10 in sequence, making it difficult, surely, to adjust the sleep patterns. Nor was there a regular weekend for family outings. Of course they also worked hail, rain or shine and he swore blind that he’d seen snow flurries on the night shift in June 1984 when we were in New Zealand, hoping for snow.

Dad was a strong union man though his union was not a large one. He could be vocal about expressing his opinions at the meetings, or so I’m told. It’s hardly a wonder, given the abysmal standards of OH&S. When the contentious 1948 St Patrick’s Day railway strike took place, Dad witnessed what happened, though I believe he was not marching. I wonder if any of his Kunkel cousins were on Police duty that day. He would use this experience to warn me against political marches in the 1960s “if I ever wanted to have children”.

The breaking point for Dad came when they introduced computerised systems. This was all too much for him and he decided it was time for retirement. The men gave him the gift of a recliner, funded from their soft-drink machine purchases…a gift that gave good service as ill-health overtook him. He also received a Railway service medal.

Eventually the coal dust and cigarettes took their toll and he had repeated bouts in hospital. Each time I returned to Darwin, I thought might be my last farewell so when the final farewell came, the impact was less of a shock. I had managed to catch a flight with minimal time and spent the last nights with him at the hospital along with my other half, and one of our daughters.

On the national stage, those few days were eventful: Kevin Rudd, and the ALP, were elected into federal government ; the Northern Territory government got a new Chief Minister, Paul Henderson, and the long-term asbestosis campaigner, Bernie Banton, also died.

The Normanby goods yard and the men’s mess room are no longer there. The men’s smoko sheds have been overtaken by a bus interchange and Grammar School buildings. Classy apartments are on the site where dad worked, and the beautiful Roma St Parklands look out over what was once a maze of shunting tracks. Next time you pass by along Countess St, or visit the Parklands, give a thought to my dad and his colleagues who gave their lives to the service of Queensland Rail and successfully delivered freight the length and breadth of Queensland.

“A good bloke” was once an Australian high compliment. Your Dad was a good bloke.

LikeLiked by 1 person

True enough – not perfect, like the rest of aren’t, but a good bloke.

LikeLike

I was reading this and thinking of the phrase, ‘salt of the earth’, though mrcassmob summed it up beautifully.. ‘a good bloke’ indeed. Reading about Roma Street brought back many memories for me also, as Dad spent quite some time there over a number of years. He was working for TNT (Thomas National Transport) and would drop off and collect freight from there constantly, in the ’60s. He would also tell us tales of some of those who were injured or worse, there… said it wasn’t for him. Dad hated being idle and would get quite frustrated about waiting in queues, but thought that the railway staff had the worst end of the stick, as they copped some of the truckies ‘grumbles.

Wonder if ever their paths crossed? We’ll never know.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for visiting and commenting Chris. I wouldn’t be surprised if they came across each other, but almost certainly dad’s uncle who was in the Goods Shed. As you say, something lost to time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have included your blog in INTERESTING BLOGS in FRIDAY FOSSICKING at

https://thatmomentintime-crissouli.blogspot.com/2017/12/friday-fossicking-dec-1st-2017.html

Thank you, Chris

I couldn’t have one without the other…

LikeLiked by 1 person

A very interesting read and a wonderful tribute to your Dad.

LikeLike

Thanks Kirrilee

LikeLike

There is a lot of recent history in your blog. It shows the trials and dangers of work even just a generation ago.

LikeLike

Thanks Marg – I’ve been meaning to write the post about dad’s workplace for a long time.

LikeLike

Being a railwayman for 49 years and one month I can relate as to how shift work affected not only our lives but that of my family and friends. Working various hours 24/7 I missed too many family occasions – including the fact that I was hundreds of miles away from home on the birth of both my children – I was interstate on trains – at one time I worked 17 Christmas days in a row -and was stuck either in Adelaide or Sydney – I was based in Melbourne – many just don’t understand the hardships shift workers face – no regular meals or sleeping patterns I existed on sleeping four hours at a time while away from home for two days – and it goes on and on.

Thanks for the wonderful story and memories you have done your Dad proud.

LikeLike

Thanks for commenting David and sharing your experience. Luckily Dad wasn’t posted out of town so he didn’t miss out on as much as you have, but I totally agree that it disrupts family lives. It’s almost certainly harder on the workers than the families too, sadly.

LikeLike

Thanks Chris.

LikeLike

A fascinating read and a noble account of what was indeed a perilous occupation. What a toll this occupation exacted on his life, with lung issues. It is a loving tribute and I am sure he is smiling on you for drawing attention to his lovely eyes.

LikeLike

Thanks Angela for your kind comments.

LikeLike